Community Shoutout: International Bird Rescue

Posted in: Conservation, Goings on

We stand in a loose half-circle around the open door of a carrier crate that was probably designed for a large dog. It is a beautiful, sunny day in the wetlands of the East Bay, and strong winds whip the grass around our feet as we prepare to watch an animal return to its home. A massive orange beak appears at the crate’s entrance, followed by a 15 pound white-feathered body. An adult American White Pelican takes a few steps out into the wetland, stops and regards us for a few seconds, and then pushes itself into the sky, taking a long flight above the body of water in front of us. The staff and volunteers from International Bird Rescue that contributed to this pelican’s return to good health all have smiles on their faces as they watch it disappear into the distance.

An American White Pelican steps back out into the wild after recovery

International Bird Rescue is a 52 year old nonprofit organization that specializes in the rehabilitation of wild waterbirds. Its origins are tied to a tragic local event—in 1971, a catastrophic spill covered 50 miles of the coastline around San Francisco with crude oil. Thousands of oil-covered birds were collected and treatment was attempted, but only a few hundred were successfully released—partly due to a lack of established protocols for oiled bird rehabilitation at the time. A few people realized that better organization and methods were needed to more successfully save birds affected by oil spills in the future, and International Bird Rescue was born. Since then, IBR has contributed to the rehabilitation of oiled birds caught in more than 250 oil spills around the world, including Alaska’s Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989, South Africa’s Treasure spill in 2000, and the explosion of Deepwater Horizon in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. Along with their international work, IBR also works tirelessly to care for injured birds in their treatment centers in the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, and Anchorage, Alaska.

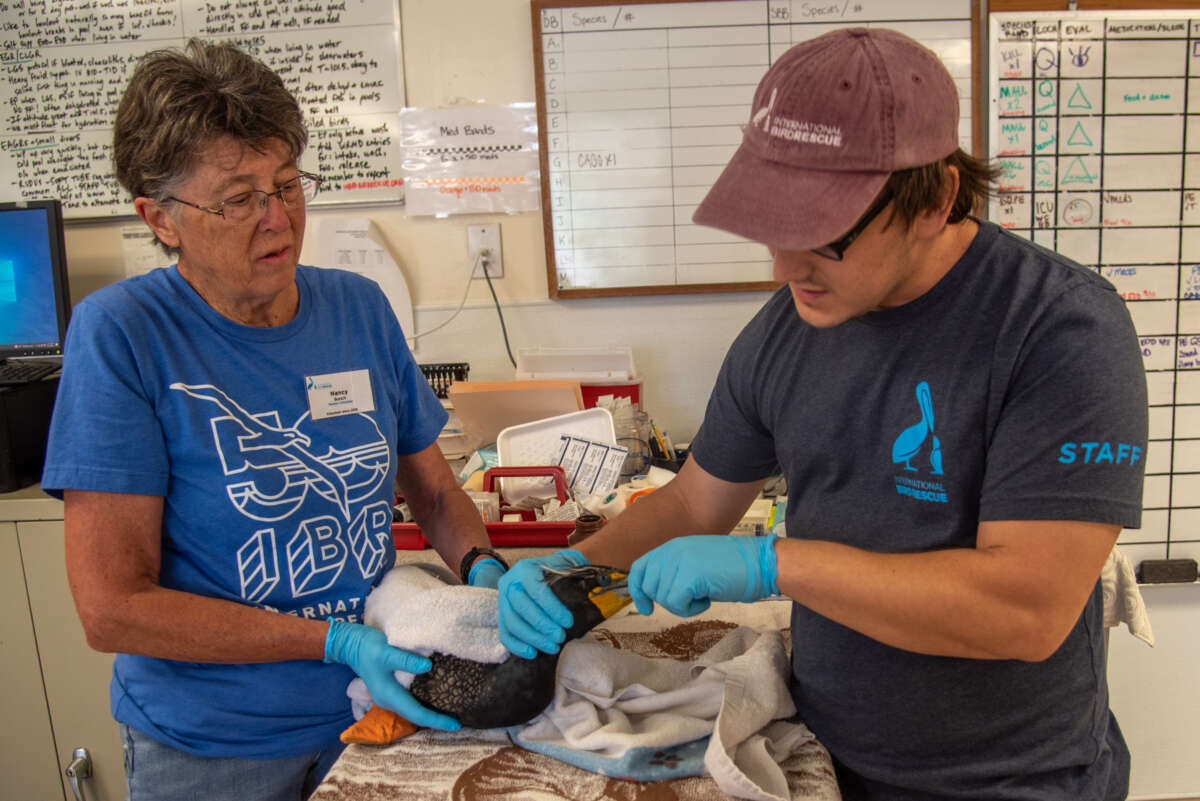

A cormorant undergoes a health check at IBR’s treatment center in Fairfield

We were lucky to catch the release of a bird, everyone at IBR’s favorite part of the job. Returning to the Bay Area treatment center after, we work backwards, using the pelican as an example to follow all of the steps in a bird’s healing journey. I am given one of the most informative tours of my life by International Bird Rescue’s CEO, JD Bergeron. JD has a deep love for birds and an excitement for the work IBR does that is shared by all of the staff we meet along the way.

JD shows us the steps of treating a bird caught in an oil spill

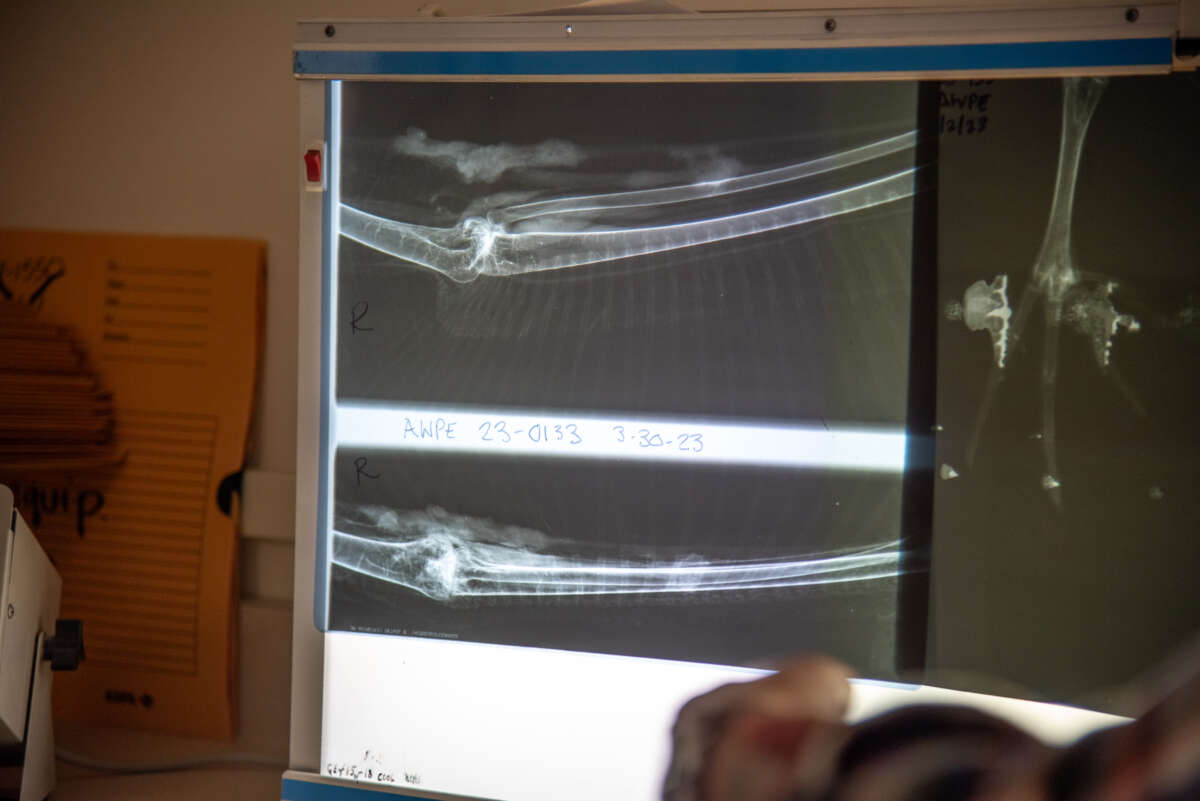

This pelican had an injury caused by a fishing hook and fishing line—the most common cause of injury that IBR deals with on a daily basis. Fishing hooks often become embedded in pelican beaks, and fishing line can cause lacerations across their body as they attempt to untangle themselves. The first step of a bird’s treatment is processing, where hospital staff examine each bird to figure out what’s wrong. This can include a physical exam for any breaks or emaciation, a white / red blood cell count to check for infection, anti-parasite treatment, and much more. For any potential skeletal problems, x-rays are also taken. Our released pelican had a prior hairline fracture that became a fully broken leg during treatment. Luckily, birds have lightning-fast metabolisms—a break that may have taken a human up to six months to heal took only three weeks on this pelican.

X-rays of the released pelican’s hairline fracture (seen running horizontally in the lower image)

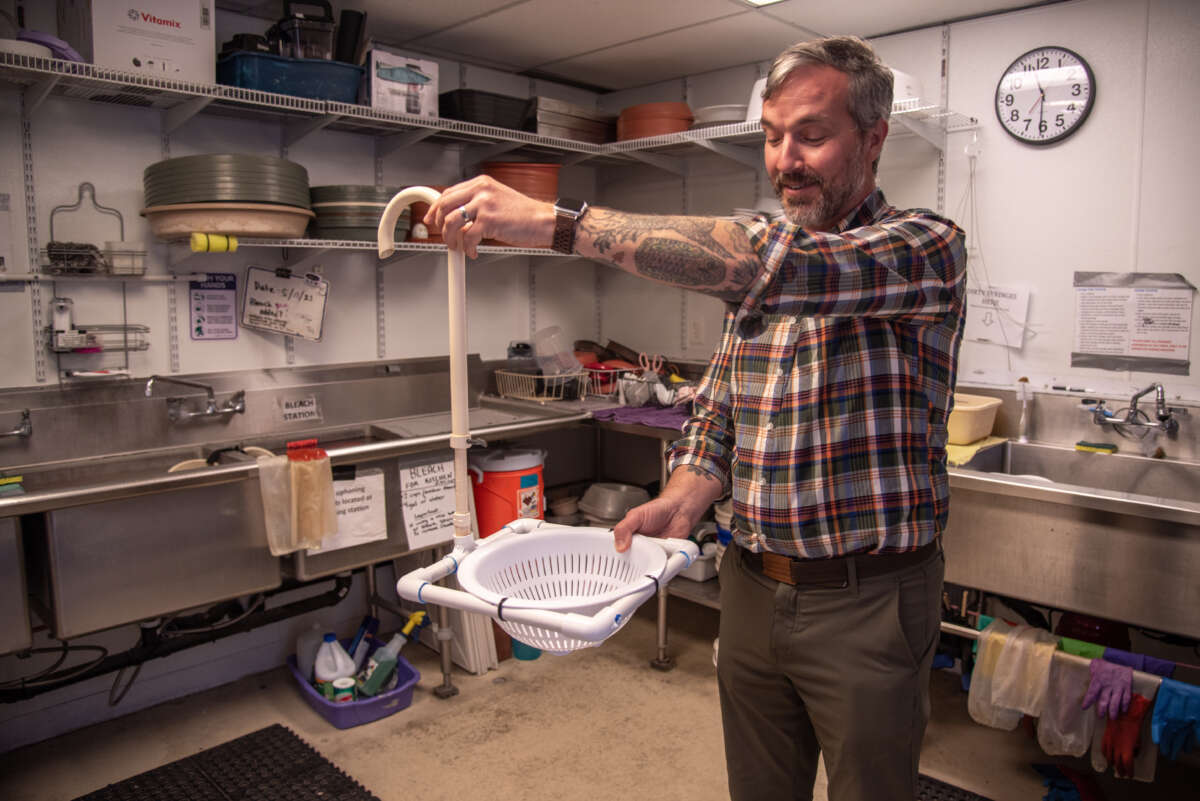

As we continue to follow our pelican’s journey through treatment, I keep discovering more and more examples of the innovation and resourcefulness that I now see as the defining characteristics of IBR’s work. In the kitchen where food for patients is prepared and distributed every day, colanders are attached to hooked umbrella handles that can be hung at just the right height to keep krill submerged in water, but still separate from the cleaner water in the rest of the pool. Many of these pools that patients spend time healing in are the massive bins used to transport tomatoes. There are drying stations as part of the re-waterproofing process after cleaning an oiled bird that appear to be fans attached to complex structures made out of gutter downspouts and PVC. JD explains to us that from feeding to housing to treatment, many of the materials and techniques used by IBR today were invented on site. “Not many people are doing what we do, so very little is tailor-made—we just adapt.”

JD shows off one of IBR’s inventions for feeding their krill-eating patients

The resourcefulness and innovation seen throughout our tour also carry over to the veterinary work happening at IBR. JD tells us that emaciated, or starving birds often lose much of the large flight muscles on their chests, to the point that the keel, the projection off of the sternum where these muscles attach, is visible. Previously, birds in this state were thought to be a lost cause. But through newly developed veterinary techniques, IBR now successfully treats these birds on a regular basis. JD tells us another story about an abandoned nest of endangered Snowy Plover eggs that were found on a local beach. The eggs were severely dehydrated, and many would have considered them a lost cause. But IBR persisted and drilled tiny holes in each egg to rehydrate them, incubated them, hatched them out, and successfully released them back into the wild. Story after story about resilience in the face of extreme adversity show me that from the top down, IBR lives by three words: every bird matters.

IBR staff and volunteer perform a health check on a cormorant patient

Why does IBR believe so strongly that every bird matters? Because they have evidence! We know that the highest chance of mortality for birds tends to be in the first few years of their lives. Individuals that have survived the perils of youth, made it to adulthood, and are of breeding age are incredibly important for the survival of their species. IBR is one of the only rehabs that is permitted to band the birds they treat, so releases can be tracked. In 1996, IBR rescued hundreds of birds from an oil spill in Alaska, including a King Eider—a gorgeous sea duck—that was found again in 2019, 23 years later. This became the oldest ever documented King Eider, and the best proof IBR could ask for that the birds they save go on to live long, healthy lives.

A King Eider male in the wild

There is so much more to say about the work of International Bird Rescue than I can cover in a short article. We learned how Dawn soap (remember those cute ducklings on their labels?) is actually all about bird rescue, donates all of the soap used for oiled bird treatment, and is working with IBR to test the effectiveness of new soap formulas on oiled birds. We discussed the current highly pathogenic strain of avian influenza sweeping the globe, and the steps IBR is taking to keep their patients safe from this deadly disease. We discussed the exciting beginnings that are currently underway for the Pacific Flyway Center, a place where IBR can lead educational walks discussing birds and the conservation of our local ecosystems.

JD explaining how IBR tracks the status of all of their patients

We also discussed how tough it can be to find funding in the field of wild bird rehab. Funding doesn’t come from pet owners the same way it would in a standard vet clinic—nobody owns these birds, so nobody is footing the bill for their treatment. Contributing to the care of wild birds at IBR’s treatment centers is reason enough to donate, but with the novel work being accomplished, donations would travel much farther than just this organization. IBR’s veterinarian, Rebecca Duerr, wants to write a variety of case studies about new treatments her team has developed, but her skills are almost always needed in the treatment of more birds, so she rarely has the time. With additional funding, more veterinary staff could be hired, case studies could be written and published in veterinary journals, and the knowledge IBR has gained could be shared much more widely. If you want to contribute to the health of wild birds, you would be hard-pressed to find an organization with more of an impact than International Bird Rescue.

A released American White Pelican prepares to take flight

On the drive back from the pelican release, I couldn’t help but think about the few moments that the pelican stopped and regarded us before flying off. JD shared one of the most common questions he gets from the public about IBR’s work, and his answer. “People always ask—were the birds grateful for the help you gave them? Did they seem appreciative? No. Absolutely not. They hate us, and that’s exactly how we want it. Hating us is what keeps them safe in the wild. It’s a thankless job, from the birds at least.” Well JD, if the birds aren’t thanking you, I will. Thank you for everything that you and the rest of International Bird Rescue does for wild birds around the world. Your work is inspiring, and we are so very grateful.

Learn more about International Bird Rescue’s work and donate at:

Photos by Nate Woodward. King Eider photo by Marion Grimm.